It’s one thing to have access to healthcare – but, it’s not always quality healthcare & it’s not designed for everyone in need.

As the pandemic rages on, and the repercussions of an inequitable crisis response are on vivid display, the lack of health care for low-income communities is one of the most pressing issues America faces today. Having access to adequate health care in low-income communities is not a guarantee as distressed populations continue to struggle with wave after wave of seemingly insurmountable barriers.

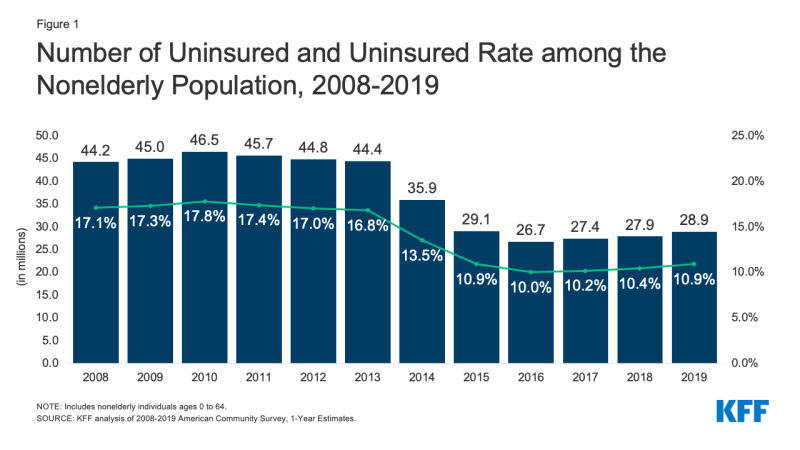

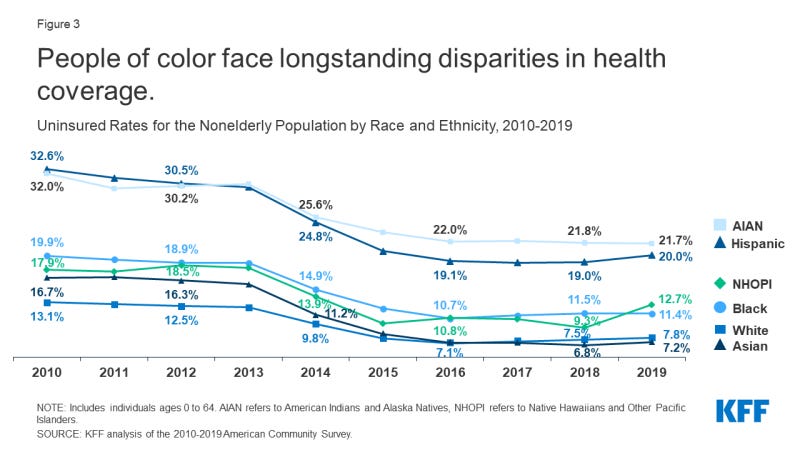

The total number of uninsured Americans has dropped substantially since passage of the federal Affordable Care Act, signed into law by President Obama and enacted in 2010. At that time, there were a total of 46.5 million Americans without health insurance or nearly 18 percent of the population; that dropped to 28.9 million in 2019 or nearly 11 percent, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (see below). A 2020 Commonwealth Fund study found the number of uninsured rose to 12.5 percent …

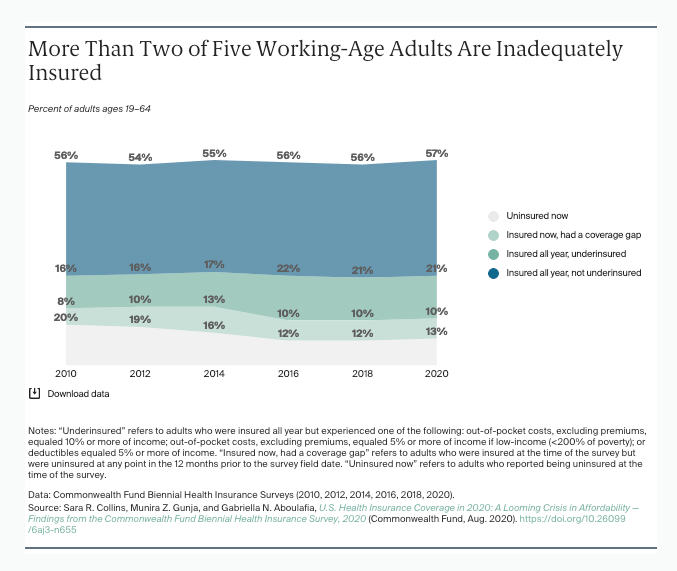

Still, having 11 percent or more of the American population suffer from complete absence of coverage is a public health and economic crisis. In addition, not all coverage is equal; many adults and families continue facing high levels of “under-insurance” even when they’re on a plan. The Commonwealth Fund estimates that’s a reality faced by nearly 45 percent of adults …

In the first half of 2020, 43.4 percent of U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 were inadequately insured. This is statistically unchanged from the last time we fielded the survey in 2018.

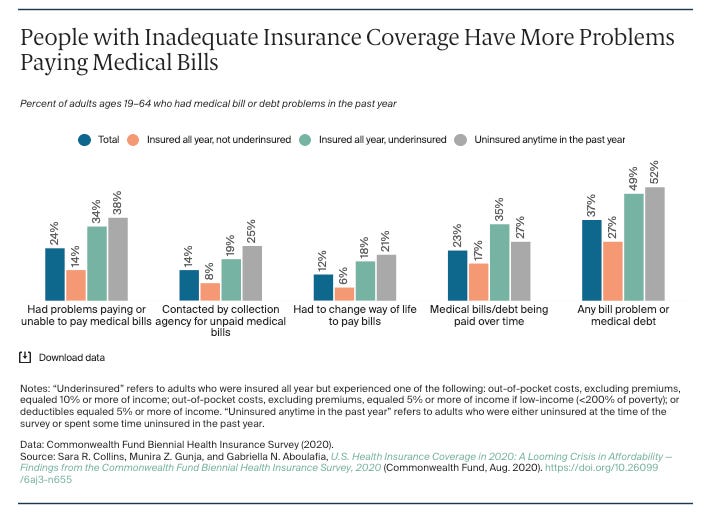

When health insurance leaves a remaining balance for the recipient to cover, unsustainable debt is now being placed onto their plate. When families are not able to cover these health care bills, they are left to deal with untreated illnesses and a mountain of debt to pay off. Even with proper medication, there are still many who are forced to pay for their own medication and, unfortunately, stuck in between hard choices over food, rent and other necessary expenses.

An increasingly challenging economic environment brought on by medical debt prompts low or moderate income populations (and even some middle class households) to not seek medical help at all, especially when it’s critical. That further compounds the problem; not seeking medical help when needed can make that medical condition worse, and a sudden health emergency attributed to reluctance not only leads to unwanted medical bills, but it also creates mounting social costs that become a drain on all communities.

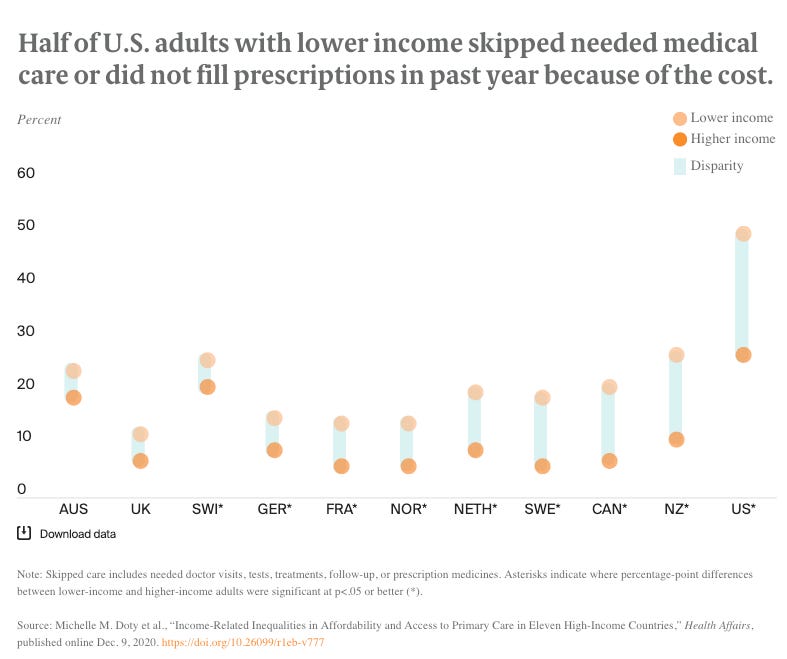

Recent findings also show alarmingly high numbers of low-income families who consider their health fair or poor compared to families with a higher income. The Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 International Health Policy Survey show’s 36 percent of low-income American adults are hit with two or more chronic conditions – which is more than in other developed countries. This is another factor which illustrates how low-income families who can not afford or access health care will most likely experience health challenges than most higher-income families.

Low-income families must also face a lower quality of care – having health insurance or access to healthcare won’t necessarily mean that care is sufficient or of a high standard. Some people may not trust their provider due to previous treatment such as racial discrimination or disrespectful engagement. A 2019 American Journal of Accountable Care study found that …

[P]hysician supply is lower in low- compared with high-income communities and that residents in low-income communities need to travel greater distances to specialty but not necessarily general acute care hospitals. Disparities in physician supply for low- versus high-income communities are greater in suburban areas and for specialty physicians. Disparities were lessened but not eliminated when we examined within-state ariation in income and provider supply. Our findings likely underestimate the extent of income disparities in access to healthcare because some physicians do not deliver services to uninsured or Medicaid patients.

These reflect tremendous equity, bias and customer experience problems in the health care systems that will require a complex set of regulatory and policy solutions. Disparities in uninsurance rates are also more pronounced among Black, Brown, Indigenous and Pacific Islander populations that require more attention.

Some solutions could include reducing the out-of-pocket cost for patients from low-income families because no one should have to worry about not having their prescription filled because they can not afford it. Affordable health coverage should also be expanded to those in dire need of health care. Another important solution that might help with this problem is income and cultural competency training for health care professionals. Providers must be required to communicate with their patients in a way that understands and empathizes with their unique socioeconomic circumstances; this is essential so patients can trust them. If a provider can display high levels of empathy to their patient, this enhances the overall experience for the patient and builds trust. Striving for a much more equitable health delivery system becomes a win-win situation for all stakeholders. Exploring these solutions now, especially while we’re in a pandemic and hospital systems are overwhelmed, presents an opportunity to get this right for the long-term.

In Partnership with TheBeNote.com